Soldiers Massacre Peaceful Protesters at Peterloo (from New Historian)

Soldiers Massacre Peaceful Protesters at Peterloo (from New Historian)

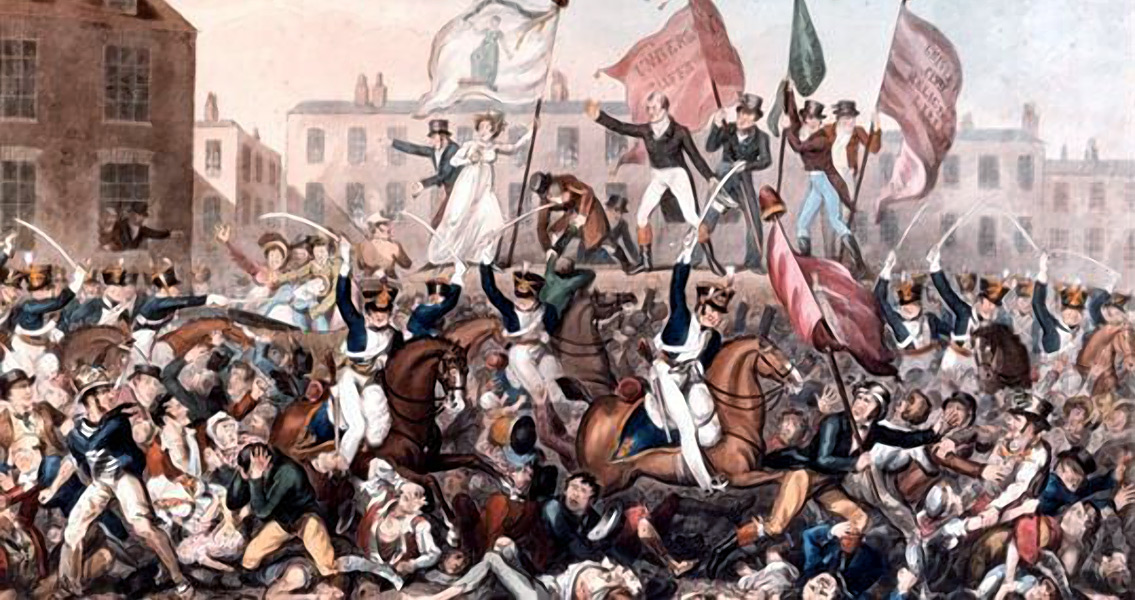

The Peterloo Massacre

On the 16th of August 1819, an event took place that shocked the political establishment to the core, and cemented Manchester’s place as a home of British Revolutionary Politics. Repercussions of the events at St Peter’s Fields (now St Peter’s Square) that day can still be felt in modern Britain. Every time someone buys a copy of the Guardian they are reading a publication born of the death of 16 protesters in Manchester, and the injuring of 600 others. If you’ve ever been “read the Riot Act” by your mother or a teacher, you have had a piece of history linked to that day shouted at you.

The Peterloo Massacre, as it came to be known, triggered a series of events that moved Manchester from the last semblances of feudalism forward to nationwide suffrage for more than just the landed gentry, and redress the balance of power in Parliament to move to greater representation.

Anger Fermenting In Manchester And Beyond

In Manchester, and around Lancashire, pressure had been growing since the end of the Napoleonic Wars in 1815. Over the previous decade the rise in the number of cotton-producing mills in the area caused a deflation in the price of textiles. In response to this, the mill owners depressed wages. Over the course of a decade, wages dropped by up to ten shillings. Exacerbating this situation were the Corn Laws which place tariffs on imported corn to protect British farmers, keeping their wheat value high. As a result, low wages and high costs left people barely able to afford a loaf of bread.

In addition to being a poor region, the people of Lancashire were also very disenfranchised. Despite mass migration to the county, it still only returned two Members of Parliament, and to vote for them you had to own land to value of around £200 (about £17,500 in modern money). Added to this was the small issue of having to travel all the way to Lancaster to shout out your vote in public – something which was not so easy in the early nineteenth century.

It was under these conditions that Political Radicalism began to take hold: the Luddites had ended their guerrilla war against new machinery a couple of years earlier, and in March of 1819 the Manchester Patriotic Union Society formed with the prime objective of reforming Britain’s and giving every working man a vote. The group were supported and spurred on by the Manchester Observer, which Henry ‘Orator’ Hunt, who would speak on the day of the massacre, described as the “the only newspaper in England devoted to such reform as would give the people their whole rights.”

Things Coming To A Head

The group’s organisers planned a meeting for the 9th August 1819, inviting supporters of reform who had garnered national acclaim such as Orator Hunt, Major Cartwright and Richard Carlile. Only Cartwright couldn’t make it. The meeting was to be one for the “whole of Lancashire.” It’s aim to be “by good management the largest assembly may be procured that was ever seen in this country.” Accounts of the day have families walking 30 miles to attend, and some estimates put the attendance around the 100,000 mark.

Shortly before the planned meeting, magistrates had taken the precaution of visiting St Peter’s Field, then a croft (an open space of land) to remove anything that may be used as a weapon, fearing a gathering could become an uprising. What was described as a “quarter load of stones” was removed from the field. The magistrates’ fear was stoked by Government spies who had intercepted Joseph Johnson’s letter to Orator Hunt inviting him to speak at the gathering. They interpreted the contents as a meeting to start an insurrection. A legal to and fro ensued as magistrates banned the 9th August meeting. Hunt et al were determined to meet, and rearranged the meeting for the 16th August. In this time, the government dispatched the 15th Hussars to Manchester to prevent any escalation on the day.

On the 16th, local magistrates met in the Star pub on Deansgate to plan what to do with Hunt and the “conspirators.” Unable to form a plan, they decanted to a house in sight of St Peter’s Field. They watched as the numbers swelled into their thousands from all around Manchester. The traditional centre of Manchester became a ghost town. Eyewitness accounts of the day claim the area around the stage was so crammed with people in their Sunday Best their hats were touching.

As Hunt’s carriage approached, the crowd became more vocal, more excitable in support of the great speaker. Earlier that day local constabulary men had attempted to form a corridor between the stage and magistrate’s view. The crowd had put a stop to this fearing it would be the route the magistrates would take to arrest the organisers and speakers. William Hulton, chairman of the magistrates dispatched two letters. One to the local military leader, and one to the Manchester and Salford Yeomanry Cavalry.

The First Casualty

The Yeomanry were made up of local traders and merchants, an armed militia there ready to the keep the peace. They received their letter first, and so charged, swords drawn towards St Peter’s Field. En route, they knocked a local pedestrian down and her two year old child became the first casualty of the Peterloo Massacre as he was thrown from her arms.

The magistrate issued the arrest warrant and six Yeomanry through the crowd to the hustings. As they got stuck in the masses, they flayed their sabres, cutting a path through the meeting to the hustings. Once they had affected the arrest, they set about cutting the many banners assembled around the stage and in the crowd. As a result, the crowd pelted at the Yeomanry with anything that came to hand.

Hulton, this time flanked by L’Estrange, the local military leader, saw this as an attack on the Yeomanry, and ordered L’Estrange to disperse the crowd. The 15th hussars covered the Eastern part of the field, the Cheshire Yeomanry the southern, and the main exit onto Peter Street was blocked by the bayonets of the 88th Regiment of Foot.

After ten minutes of confusions, struggle, and dispersion, the field was cleared of the protestors, aside from the dead, the injured, and those tending to the injured. Initial estimates put casualties at 11-14 dead and 600 injured. It is widely accepted that many of the injured did not come forward for fear of reprisal from local law enforcement, or their bosses who owned their mills.

Rioting around Manchester continued through the day, and in towns as far as Stockport and Macclesfield it continued on the 19th.

Shaping The Future

Peterloo’s legacy includes an awaking in British politics; one we can still draw parallels to today. It is widely regarded as one of the first times national press reporting had an influence, as reporters from London, Leeds and Liverpool were all there to record events first hand. The nation was able to learn about the events of the day, and as a consequence were able to feel the indignation that Manchester itself felt. Much like today, where we are able to see minute by minute updates on events through social media, reporting had been revolutionised. The term “Peterloo” was actually coined by the Manchester Observer in an article that would sell out for 14 consecutive weeks.

The wider political reform that had been hoped for as a result of the original meeting would take much longer to develop. Following trials for sedition, and subsequent imprisonment, the government hoped it had quelled calls for reform, when all it had done was hold it at bay. It would be another 13 years before there was any real electoral change, but the result would be nearly 100 years of progressive change, eventually resulting in universal suffrage in 1928.